A growing number of white-collar convicts, including former FTX CEO Sam “SBF” Bankman-Fried, are exploring pathways for clemency following the election of US President Donald Trump. However, as pardon backlogs continue to grow, the chances of conviction relief remain slim, according to William Livolsi, executive director of White Collar Support Group — a nationwide support organization that advocates for fairer post-conviction policies.

Clemency requests on the rise following Ross Ulbricht pardon

On Jan. 22, President Trump followed through on his campaign promise to pardon Ross Ulbricht, who was sentenced to 40 years plus two life sentences for creating and operating the Silk Road darknet marketplace. For Bitcoiners and Libertarians, Ulbrich’s 2015 conviction was overly harsh and emblematic of extreme government overreach.

Shortly after Ulbricht was pardoned, reports surfaced that Sam Bankman-Fried’s parents were exploring the possibility of a presidential pardon for their son, who was sentenced to 25 years in prison following the collapse of his crypto empire.

SBF’s parents are Stanford University professors Joseph Bankman and Barbara Fried. Source: New York Post

However, “the comparison between Ulbricht and SBF isn’t entirely straightforward,” said Livolsi. “Sure, both are high-profile figures in the crypto space, but their individual cases, and the sentences imposed in each, are very different. Additionally, Ulbricht’s clemency was publicly tied to the campaign promise President Trump made to his political supporters.”

“At the end of the day, no one really knows all the factors that might influence [a clemency] decision,” he said.

No clear process

The Office of the Pardon Attorney has established a formal application process for clemency requests, which begins with a clemency petition and ends with a formal recommendation from the Pardon Attorney. It’s then up to the president to decide on each individual case.

However, what seems straightforward on paper becomes extremely opaque after the petition is submitted. As Livolsi explained, the petition backlog sitting at the Office of the Pardon Attorney is roughly 10,000.

For a long time now, the role of the Office of the Pardon Attorney “has been largely ignored,” said Livolsi. “Instead, presidents have granted pardons based on political connections, media pressure, or personal interest.”

How clemency petitions are supposed to work. Source: Office of the Pardon Attorney

This opacity is one of the biggest pain points for the White Collar Support Group’s more than 1,100 members. Their frustration cuts across presidential administrations.

“Whether it was President Trump or former President Biden, the clemency process hasn’t felt like it follows a clear, merit-based system for some time. It’s become more about who you know rather than about a fair, structured process.”

Related: Silk Road founder Ross Ulbricht thanks Trump for full pardon

Ross Ulbricht tastes freedom for the first time in 12 years. It’s unclear whether other clemency petitioners will enjoy the same fate. Source: Free Ross

So, while white-collar convicts may be hopeful under President Trump, there’s very little to suggest that clemency petitions will be prioritized unless there’s a political motive behind them.

“For people without political connections or media attention, it feels like their chances are slim,” said Livolsi. “Some still hold out hope that President Trump might grant clemency to more white-collar individuals, but the unpredictability of the system makes it tough to have confidence in the process or the outcome.”

Prison often leads to debanking

When Ulbricht was finally released from prison, the Free Ross campaign had amassed more than $270,000 worth of Bitcoin (BTC) donations to help the Silk Road founder get back on his feet. That’s on top of the 430 BTC held in wallets associated with Ulbricht, according to Coinbase director Conor Grogan.

Source: Cointelegraph

However, most individuals who are released from prison don’t have a Bitcoin stash to fall back on. Many face serious debanking challenges, including account closures, credit card denials and financial blacklisting.

“Debanking […] is a huge issue that doesn’t get enough attention,” said Livolsi. “People with a conviction history, especially in white-collar cases, often find themselves shut out of the financial system entirely.”

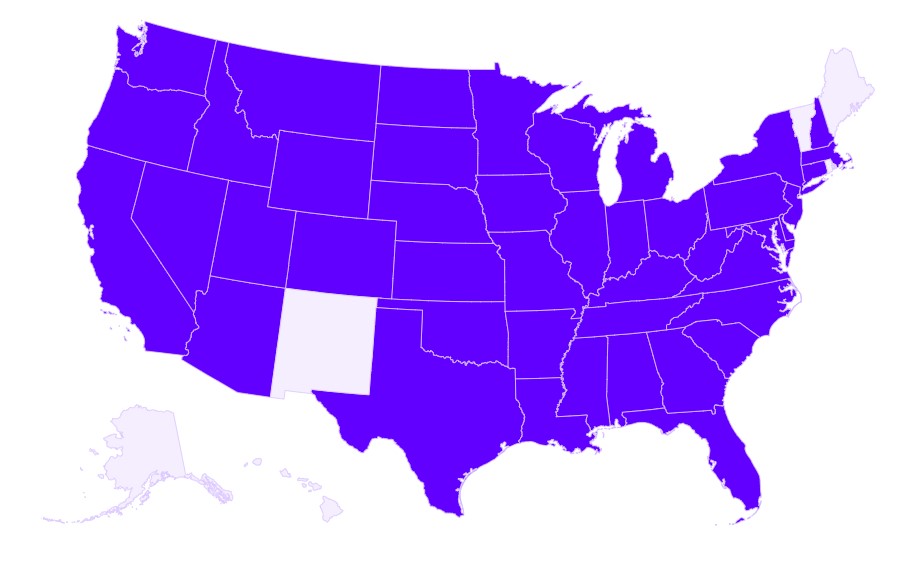

While some US states have consumer protection laws that limit how long banks and employers can hold a conviction against someone, “there are no real protections” at the federal level, said Livolsi.

In practice, this “means financial institutions can impose lifetime bans with no oversight or appeal process.”

The White Collar Support Group has established the Right to Banking Initiative to ensure that everyone has access to financial services, regardless of their past.

Magazine: $3.4B of Bitcoin in a popcorn tin: The Silk Road hacker’s story