MEXICO CITY — At the entrance to Mexico City’s largest park lies a towering marble monument to six young military cadets killed in battle.

The Niños Héroes — “boy heroes” — died while defending Mexico’s capital during the Mexican-American War, which broke out 179 years ago this week.

That conflict may not loom large in the minds of most Americans. But in Mexico, which in defeat was forced to cede more than half of its territory to the U.S., memories of the war and other military quarrels with the nation’s powerful northern neighbor remain deeply felt.

As Mexicans, we have to unite for this new battle — which is a trade war

— Felix de la Rosa, chemical engineer

Today, Mexico is once again locked in battle with the United States, this time facing an American president who is hurling insults, tariffs and threatening U.S. drone strikes here. Many see it as just the latest chapter in an age-old tale of U.S. aggression.

“In Mexico there’s a perception that the United States is the villain of our story,” said historian Alejandro Rosas. “That’s the narrative you grow up with, it’s what they teach you in school. We’ve been victims of the United States forever.”

The Niños Héroes are often viewed as the embodiment of courage, teenagers who fought like men against a northern invader. Their faces have appeared on currency, Streets bear their names, children learn about them in school.

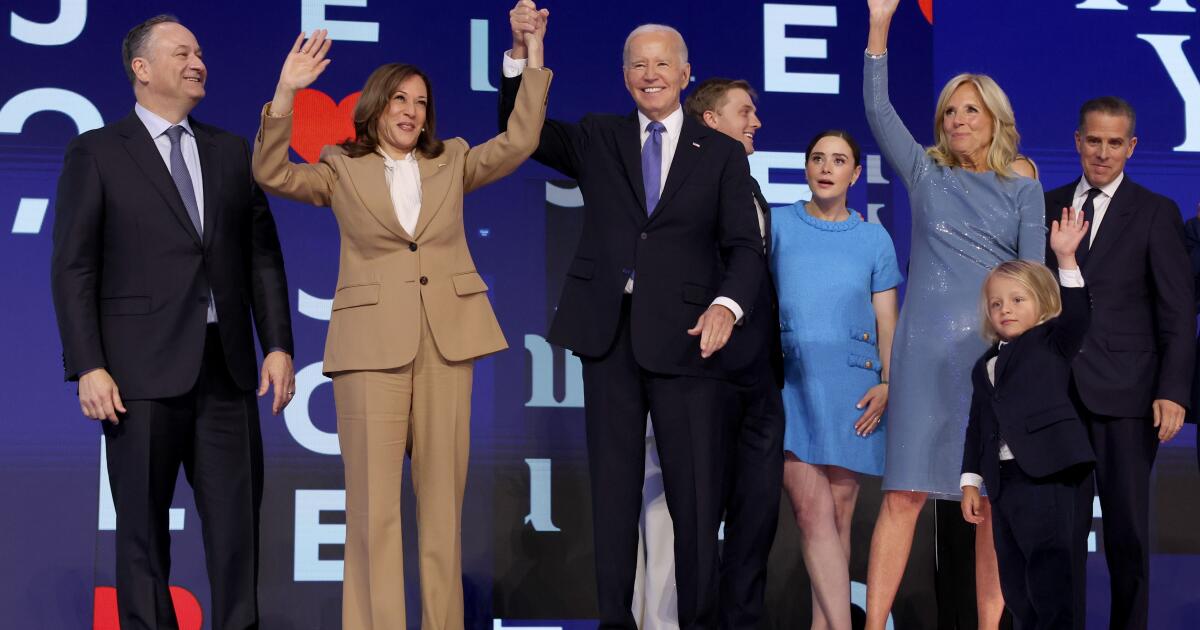

Then-Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his wife Sophie Gregoire Trudeau attend a wreath-laying ceremony at the Niños Héroes monument in Mexico City’s Chapultepec Park on Oct. 12, 2017.

(Eduardo Verdugo / Associated Press)

At the white marble monument in Chapultepec Park, which this week was crowded with families enjoying spring break, many stopped to take pictures in front of the monument where the remains of the Niños Heroes are entombed.

“It’s unfair,” said Monserrat Martínez Hernández, 20, a college student who snapped selfies alongside her mother, sister and two cousins.

“They already took away half our territory,” she said of the United States. “Now they want to abuse their power again, this time from an economic perspective.”

Since Trump took office in January, Mexico has been seized by a wave of nationalistic zeal.

On TikTok, users have demanded a boycott of American products, filming themselves pouring Coca Cola down the drain. Companies have embraced the red, green and white of the Mexican flag in ad campaigns.

After the government announced a relaunch of the “Hecho en Mexico,” or “Made in Mexico,” seal on locally produced products, Grupo Modelo said it would print the slogan on its beer bottle caps.

Thousands of people gather to take part in a massive boxing class for the peace and against addictions, organized by Mexican authorities in order to motivate people to live a healthy lifestyle and to stay away from drugs, at the Zocalo main square in Mexico City on April 6.

(Daniel Cardenas / Anadolu via Getty Images)

Leading the way is Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, who has both stoked — and benefited from — the surge in national pride.

In the face of Trump’s repeated attacks, Sheinbaum has had to walk a thin line, appeasing him enough to try to avert potentially catastrophic tariffs while also showing fellow Mexicans that she is defending national sovereignty.

She has cooperated with Trump on several key measures, sending thousands of National Guard troops to fortify the northern border and transferring dozens of suspected cartel members wanted by the U.S.

But she has pushed back when possible, suggesting Mexico would retaliate if the Trump administration carried out drone strikes in its territory, pushing a constitutional measure that effectively bans the planting of U.S. GMO corn and recently asking television stations to pull what she called “discriminatory” ads produced by the Trump administration warning against undocumented migration. Her approval ratings — which hover around 80% — are among the highest in the world for a head of state.

She seems to work the word for sovereignty — soberano — into almost every speech.

Tellingly, she has often invoked history in her effort to rally support.

This month she marked the anniversary of the sixth-month long U.S. occupation of the port city of Veracruz in 1914.

“Mexico is and always will be a great country,” Sheinbaum told a stadium filled with smartly dressed naval officers. “We are neither a protectorate nor a colony of any foreign nation.”

Recently, Sheinbaum used the word “traitor” to describe an opposition party member who voiced support for a U.S. effort to designate drug cartels as “terrorist” groups. She compared him with the conservative Mexicans who, in the 1850s, invited the French to help overthrow the liberal government of President Benito Juarez. The French ended up occupying Mexico for several years, briefly installing Ferdinand Maximilian Joseph, an Austrian duke, as emperor.

A supporter of presidential candidate Claudia Sheinbaum takes a selfie with a campaign poster during Sheinbaum’s closing campaign rally at the Zocalo in Mexico City on May 29, 2024.

(Matias Delacroix / Associated Press)

But it is the history of U.S. antagonism, with its roots in manifest destiny and President Polk’s obsession with territorial expansion, that Mexicans best remember. In 1845, the U.S. annexed Texas, a move Mexico rejected. After Mexican troops attacked U.S. soldiers in Texas on April 25, 1846, the U.S. formally declared war. The 1847 battle over Mexico City is recalled on the U.S. side in the opening line of the Marines’ Hymn: “From the Halls of Montezuma …”

The U.S. and Mexico share a 2,000-mile long border and deep cultural, economic and family ties. Americans are largely welcomed with open arms and warm hospitality when they visit Mexico’s vibrant cities, archaeological ruins and vast beaches.

But if an undercurrent of hostility is at times detectable, Rosas says it is related to how Mexicans are educated about their history. While neighboring countries often have territorial disputes, he said Mexican governments, particularly those associated with the Institutional Revolutionary Party, made the U.S. the boogeyman in order to drum up domestic support, he said.

“They needed a shared enemy,” Rosas said. “So they embraced very defensive, nationalistic and anti-interventionist politics.” It’s no mistake, he said, that the war between the U.S. and Mexico is often referred to as “the United States intervention.”

At the Niños Héroes monument, Mexicans reflected on that past and possible conflicts — economic ones — looming in the future.

Felix de la Rosa, 64, a chemical engineer from the state of Coahuila, which borders Texas, says he visits the monument every time he’s in Mexico City.

“As Mexicans, we have to unite for this new battle — which is a trade war,” he said. “But we shouldn’t bow our heads without fighting. I think the boy heroes are a great example, and that is how we should act, with great courage and dignity in the face of this new battle.”

But for some, the lesson of history is that Mexico may again suffer the fate of being neighbor to one of the most powerful countries in the world.

“The truth is, our country doesn’t have the economic strength they have,” said Gerardo Santos, a 33-year-old businessman. “Our country is weaker, and President Trump knows this and takes advantage of it.”

“In the end, the gringos will win again,” he said. “There’s nothing we can do about a man like Trump. The guy is crazy.”