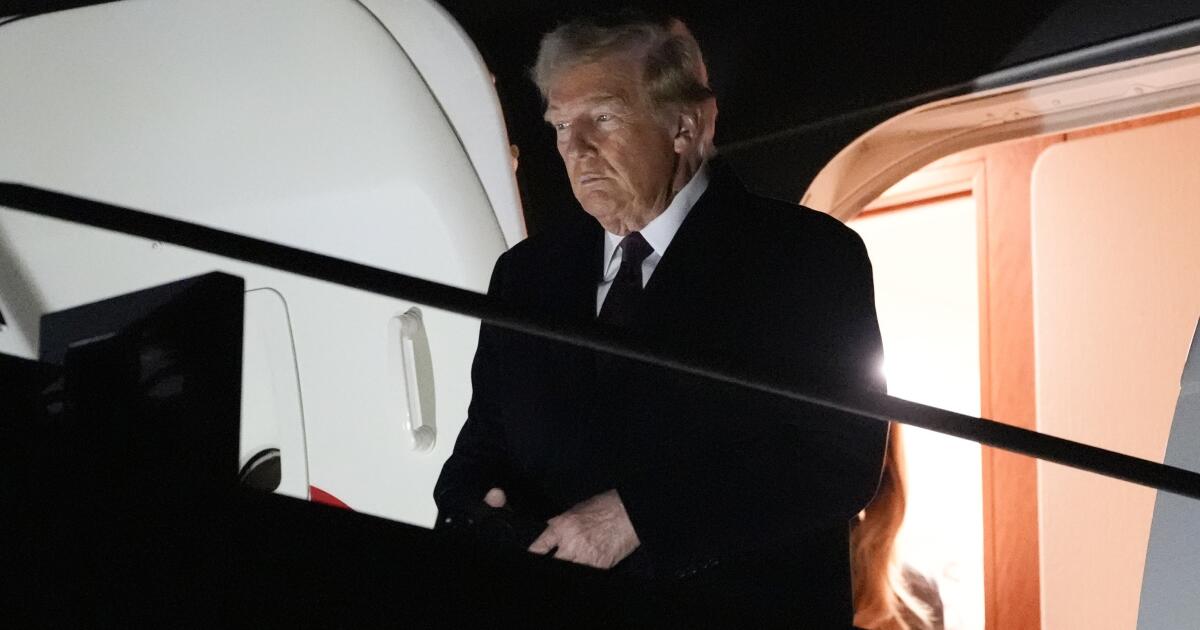

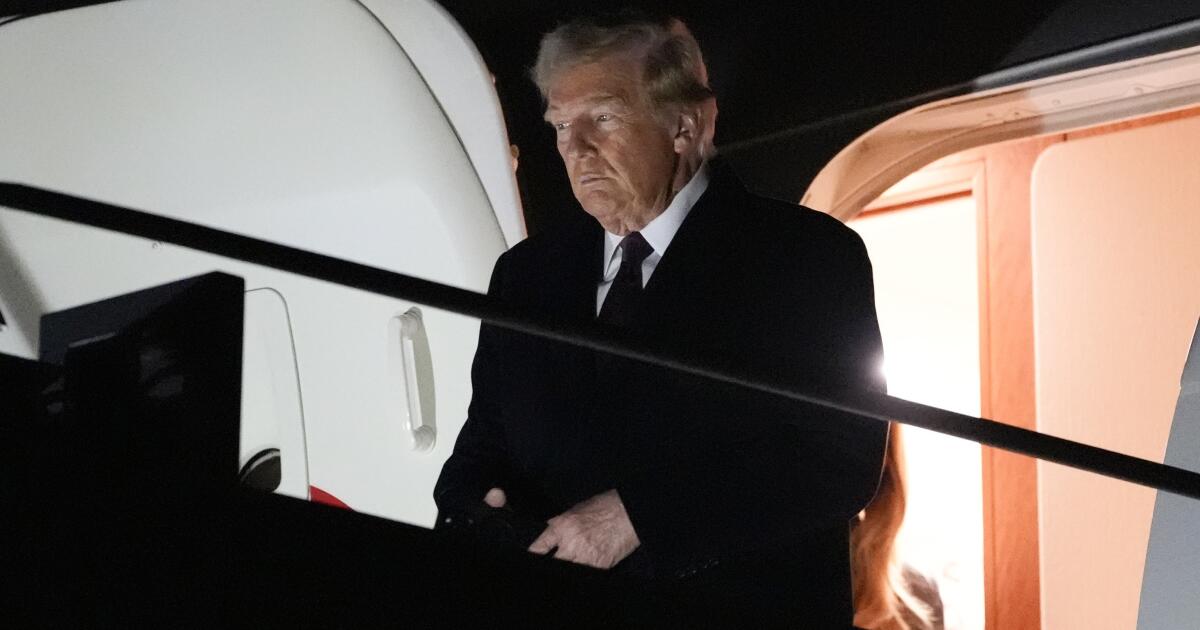

WASHINGTON — As Donald Trump takes the oath of office Monday for the second time, the world is watching with a mix of fascination, curiosity, elation or dread — and a sense that this time around, those outside the United States perhaps have a better idea of what to expect from his presidency.

Even before Inauguration Day, the 2½ months of transition since Trump defeated his Democratic rival, Vice President Kamala Harris, had already yielded head-spinning developments on the global scene.

Some of America’s closest traditional allies were jolted by the president-elect’s rhetoric evoking an expansionist 19th century ethos, delivered via modern-day social media blast. Populist figures, already emboldened by a tidal wave of anti-establishment electoral sentiment, have found a congenial reception in Trump’s orbit.

And autocratic governments are anticipating a far more transactional relationship with Washington, unburdened by diplomatic discourse about human rights or the rule of law.

Trump may be the most mercurial American president in decades, but embedded in that is a certain element of predictability: that nearly any long-standing international norm may well fall by the wayside. The keenly felt fragility of a post-World War II rules-based order is its own kind of road map, some veteran observers suggest.

Many foreign leaders “are no longer scrambling to figure out what to do,” said Daniel Fried, who spent nearly four decades as a U.S. Foreign Service officer.

“They know they have to plan for all contingencies,” said Fried, now with the Atlantic Council think tank. “They have a better sense this time, though it still rattles them.”

Trump’s heavy footfall in the final days before assuming office almost certainly brought about the finalization of a cease-fire and hostage-release agreement in the devastating war in the Gaza Strip. The deal drafted by the Biden administration was to take effect the day before Trump’s swearing-in.

Though Trump has backed off on a boast that he would halt the fighting in Ukraine in 24 hours, there is a sense among all involved parties that Trump’s presidency will alter the trajectory of the nearly three-year-old full-scale Russian invasion of its sovereign neighbor.

Then there’s China. The upheaval triggered by the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that the immensely popular short-video app TikTok must sever ties with its Chinese parent company or face a U.S. ban will likely surface some insights into future dealings by Washington and Beijing over accelerating technological, trade and military rivalries.

“China could be a big surprise” under Trump, said Michael Cox, an emeritus professor of international relations at the London School of Economics. One factor to watch closely, he said, were the “huge” business interests in China of the world’s wealthiest man, Elon Musk, a prominent but relatively new figure in Trump’s orbit.

Musk, the SpaceX and Tesla billionaire, also has Trump’s seeming imprimatur as he shocks close partners like Germany and the United Kingdom with verbal broadsides against their elected leaders and highly amplified backing for domestic far-right forces.

With Germany’s election just over a month away, Trump has raised no objection as Musk has used his social media platform, X, to tout the far-right party Alternative for Germany as a national savior. Chancellor Olaf Scholz again Friday branded Musk’s electioneering “completely unacceptable.”

In Britain, in an upending of the decades-old “special relationship,” Musk has urged the release of a notorious jailed anti-Muslim extremist, Tommy Robinson, and loudly declared that Prime Minister Keir Starmer belongs in jail. All met by silence from Trump.

“It all sends a very disturbing message to Europe — to people friendly to the United States,” said Cox, who is also with the British think tank Chatham House.

Underscoring the populist-friendly tone of the new administration, expected inaugural attendees include Italy’s far-right Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni and British firebrand politician Nigel Farage. Hungary’s prime minister, Viktor Orban, who had endorsed Trump as a “man of peace,” was invited but could not attend, Hungarian media reported.

As Trump, Musk and their team have done in Europe, they have already signaled their approach to Latin America and where they will place their favors. Trump was courting Latin American leaders accused of human rights abuses and antipathy to democratic norms even before he won election.

Argentinian President Javier Milei, who styles himself after Trump and vowed to take a “chain saw” (which he often wielded at rallies) to his country’s government and institutions, is invited to the inauguration. So is El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele, who calls himself the world’s coolest dictator and engineered a second term in office despite a constitutional prohibition. Bukele also adopted bitcoin as a national currency, is profiting in crypto circles and said to be admired by Musk.

Allies of Trump have sought to undermine democratic leftist governments in Latin America, such as Guatemala and Colombia, and will likely reverse President Biden’s last-minute diplomatic concessions to Cuba that included taking it off the U.S. list of sponsors of international terrorism, a designation that advocates considered unfair and that damaged the struggling Cuban economy.

Mexico and Panama will be especially vexed by Trump.

Their presidents, Claudia Sheinbaum and José Raúl Mulino, respectively, are seeking a way to placate some of his demands, such as slowing illegal immigration that originates or passes through their countries, while standing up to ideas that they see as a threat to national sovereignty.

Trump has entertained declaring Mexican drug cartels as foreign terrorist organizations, a designation that could be used to attack them militarily inside Mexican territory. He has also said he wants to take back control of the Panama Canal, a vital waterway that the U.S. once controlled as an American colony on foreign soil but was turned over to Panama in a treaty signed by then-President Carter in 1977. Trump declined to rule out using the military to seize the canal.

Trump’s nominee for secretary of State, Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), has stopped short of echoing some of Trump’s most unorthodox views but largely supported an “America first” agenda, saying every policy decision must face three questions: “Does it make America safer? Does it make America stronger? Or does it make America more prosperous?”

In the Middle East, dramatic events surrounding the cease-fire breakthrough between Israel and the militant group Hamas were drawing “split-screen” comparisons with the 1981 inauguration of Ronald Reagan, when U.S. hostages held in Iran were freed moments after the new leader took the oath of office. The presidency of Reagan’s predecessor — Jimmy Carter, who died Dec. 29 — was heavily shadowed by the long effort to free them.

With the first of the hostages due to be freed as soon as Sunday, Trump was quick to trumpet his own role in securing the accord. Announced Wednesday and finally ratified by Israel’s Cabinet early Saturday, the pact calls for a phased handing over of remaining captives, living and dead, seized by the Hamas fighters who surged into southern Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, killing about 1,200 people.

Israel’s bombardment of Gaza over the following 15 months has killed more than 46,000 Palestinians, according to Gaza health officials, leaving the territory in ruins and displacing about nine-tenths of its more than 2 million people.

“This EPIC ceasefire agreement could have only happened as a result of our Historic Victory in November, as it signaled to the entire World that my Administration would seek Peace and negotiate deals to ensure the safety of all Americans, and our Allies,” the president-elect wrote in a social media post as the breakthrough was being formalized.

Biden, for his part, acknowledged the unprecedented cooperation between Trump’s team and his own diplomats in the final push toward an accord, but could not contain himself when a reporter asked him last week if the president-elect was right to take full credit.

“Is that a joke?” he asked.

Many people in Greenland thought Trump was joking during his first presidency when he spoke of acquiring the vast island territory that is part of Denmark. But he has resurfaced the idea, refusing to rule out using military force to seize control “for the purposes of National Security.”

Europe quickly pointed out that Trump would be attacking European borders and a NATO ally.

“We have been cooperating for the last 80 years [with the U.S.] and … have a lot to offer to cooperate with,” Greenland Prime Minister Múte Egede said, “but we want also to be clear: We don’t want to be Americans.”

Fried, at the Atlantic Council, cautioned that “it was not good for the United States to have other states hedging their bets.” You never know, he said, when the U.S. will need its allies.

“I personally would take him both literally and seriously,” said Belgium-based analyst Guntram Wolff, playing off the popular political trope from Trump’s first presidential campaign, when observers parsed the difference between how his supporters and adversaries interpreted his more provocative utterances.

But he acknowledged that the world will simply have to wait and see what four more years of Trump will bring.

“He has an agenda; he makes strong points,” said Wolff, a senior fellow at Bruegel, a Brussels think tank. “And he’s been elected.”