SAN FRANCISCO — In early 2020, Albert Jones was sitting in his cell on San Quentin’s death row, as he had every day for nearly three decades, when reports of a mysterious respiratory illness started to circulate.

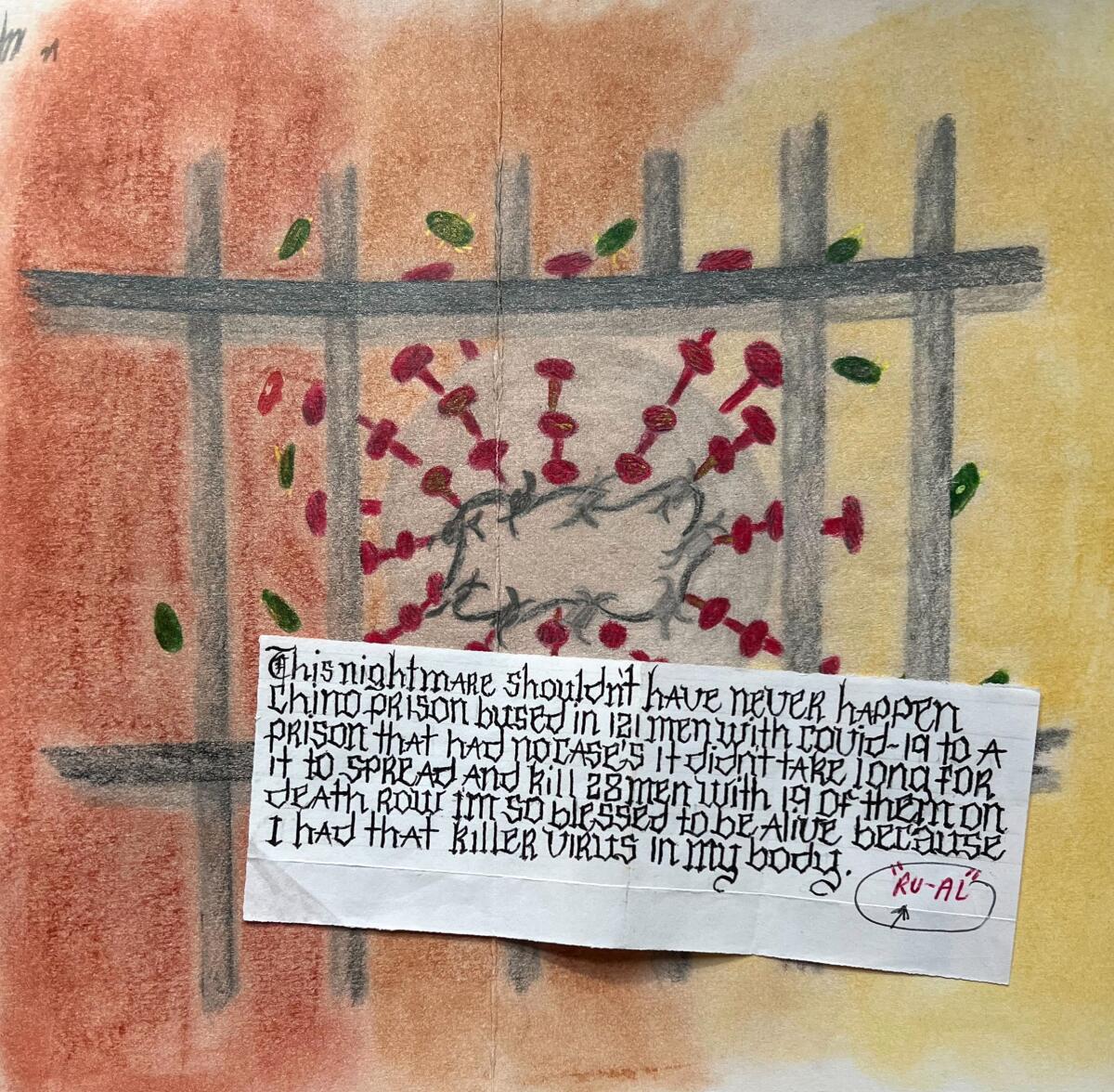

In the following months, hundreds of death row inmates fell sick as COVID-19 swept through San Quentin State Prison‘s east block, the crowded warren of concrete and iron cells, stacked five stories high, that for decades housed many of California’s most notorious criminals. By the end of August 2020, more than 2,200 prisoners and 270 staff members at San Quentin had fallen ill. One officer and 28 inmates died from their illness, including at least a dozen condemned men.

Through it all, Jones kept detailed journals chronicling his anxiety over catching the “killer virus.” And when he did contract COVID, he recounted his agonizing recovery.

“I Survived COVID-19” is one of several books that inmate Albert Jones has self-published during his years on death row.

(Courtesy of Albert Jones)

“The world is on lock-down. This state is on full lock down,” Jones wrote at the start of the pandemic. (The entries quoted in this article appear with the punctuation and spelling used in the journals.) “This disease is spreading so fast people don’t know what to do so staying in their home is all they can do and watch T.V. like me.”

“Scott was my next door neighbor for 12 years,” Jones wrote that summer, referencing rapist and murderer Scott Thomas Erskine, who died in July 2020 after contracting the virus. “We had just showered and the nurse gave him his medications and then they see how pale his skin was and loss of weight so they took his oxygen level and it was 62 so they took him out of his cell and put him on oxygen and rolled him off. Three days later he died.”

In 2023, Jones published a memoir he titled “I Survived COVID-19,” one of 10 books — two of them collections of prison recipes — that he has written during his years behind bars.

Jones, now 60, was sentenced to death in 1996 for the brutal double murder of an elderly couple during a robbery in their Mead Valley home. He has lost an appeal of his conviction, but maintains his innocence and continues to work with his attorneys on new grounds for appeal.

Jones has nonetheless embraced a sense of purpose in prison, documenting community life on San Quentin’s death row through writing and art. He has been held up as a model prisoner and met with Gov. Gavin Newsom last summer when the governor was on site to showcase his efforts to refashion San Quentin and other state prisons with a more dedicated focus on rehabilitation.

Jones’ earnest musings are now poised to find an unexpected spotlight and far broader audience. A Sonoma County bookseller who sees Jones’ collected works as a rare glimpse into one of America’s most notorious cell blocks is auctioning some of his writing and prison memorabilia at a posh New York City book fair this month. The archive will be on display Thursday through Sunday at the New York International Antiquarian Book Fair, an event expected to draw curators from museums and research institutions, as well as private collectors. The asking price is $80,000.

“There is no other archive like this in existence,” said Ben Kinmont, the Sebastopol bookseller representing Jones in the sale.

Condemned inmate Albert Jones has written two cookbooks, featuring recipes that can be made in a prison-sanctioned electric pot.

(Courtesy of Albert Jones)

Jones’ books — chronicling his gang life in Compton, his spiritual journey as a condemned man and recipes doable with a prison-sanctioned electric pot — make up the bulk of the collection. But the archive also includes personal items, such as an old pair of reading glasses, a broken wristwatch and his “prison eye,” a strip of cardboard with a piece of reflective plastic attached to the end that prisoners would stick through the bars of their cells to see whether guards were coming.

In an interview from prison, Jones said the collection stems from his efforts to leave a record of his incarceration, and a hope that his daughter and grandchildren might remember him as something more than a prisoner.

“I want to be remembered as, first of all, a human being that made mistakes,” Jones said. “I didn’t understand what I was going to do with the rest of my life, knowing that the state wanted to kill me, as if I wasn’t nothing.

“I do have worth,” he said.

California hasn’t executed a prisoner since 2006, and Newsom issued a moratorium on the practice in 2019. Last year, Jones was transferred out of San Quentin after Newsom ordered prison officials to dismantle death row and integrate the condemned prisoners into the general populations at other state institutions. Jones is now housed at California State Prison, Sacramento.

The fact that San Quentin’s death row is in effect extinct makes Jones’ work historically relevant, Kinmont said.

Bookseller Ben Kinmont says he marveled at how Albert Jones’ first cookbook included not only recipes collected from men on death row, but also directions for how to enjoy meals “together.”

(Hannah Wiley / Los Angeles Times)

As a bookseller who specializes in works about food and wine written from the 15th century to early 19th century, Kinmont wasn’t exactly looking for a death row client when Jones wrote him a few years ago looking for help in selling his first cookbook, “Our Last Meals?” But the pitch came at an opportune moment.

Kinmont was exploring the relationship that people living in poverty have to food and the value of coming together for a meal. Working with Jones seemed an interesting avenue for probing that theme.

Kinmont marveled at how Jones’ cookbook included not only recipes collected from men on death row, but also directions for how to enjoy meals “together.” His gumbo recipe, for example, calls for two pouches each of smoked clams, oysters and mackerel along with white rice, oregano, cumin and chile peppers. Mix in some diced onions and bell peppers, and throw the mixture into an electric pot with a sausage link. Once the dish is ready, Jones would transfer individual servings into plastic bags. A prisoner from a cell above would send fishing line down to Jones, who would tie up the bag and send it back up.

“These guys are asserting their humanity through trying to prepare food as best they can, through the care package system that’s available to them,” Kinmont said.

Kinmont ultimately sold the cookbook to UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library for $20,000.

Jones has used his time in prison as an opportunity for growth and earned his college degree behind bars.

(Courtesy of Albert Jones)

Jones said he made about $14,000 off the sale — a far cry from the occasional proceeds that trickle in from one of the self-published books he offers for $15 on Amazon. Jones sent some of the money to his daughter and grandchildren in Georgia, and bought new prison garb for himself and friends. At Christmas, he put together gift bags with hygiene products for dozens of men living in his unit.

If the new archive sells in New York, he hopes to use his cut to open a trust fund for his four grandchildren and help his daughter buy a house.

“I know I got blessed,” he said, “so now it’s time for me to start blessing other people.”

Still, the arrangement raises ethical questions about who should benefit from work prisoners do behind bars.

Jones was convicted of hog-tying and stabbing to death James Florville, 82, and his wife, Madalynne Florville, 72, during a 1993 home invasion. California previously prohibited prisoners from financially benefiting from selling their crime stories, but in 2002, the state Supreme Court struck down that law.

Still, after The Times contacted her for comment on this article, Terri Hardy, a spokesperson for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, said the agency had not been informed about a contract to sell Jones’ books and, as a precaution, would alert the Florvilles’ family members. She cited a provision of the state penal code that requires the prison system to “notify registered victims or their families in cases where an incarcerated person enters into a contract to sell the story of their crime.”

In phone interviews with The Times, members of the Florville family expressed outrage at the notion of Jones profiting from his prison writing.

“What makes him get the right to write any book?” said the couple’s daughter-in-law, Mary Moore, reached at her home in Southern California. “My children, their grandchildren, lost their grandparents. They were very loving people. My father-in-law would have given you the shirt off his back, and so would have Madalynne.”

“I believe in an eye for an eye,” said Moore’s daughter, Rena MacNeil. “This is an ongoing thing every day. I sit and think about my grandparents and what they went through.”

Jones said his intention is not to get into details of his conviction, but to provide his family a written record of his life and financially support them.

“If they feel that I’m doing the wrong thing for my grandkids, then so be it,” Jones said. “I know there’s going to be those critics, there’s going to be those ones that say you shouldn’t receive this, or you shouldn’t get this. That’s OK. Because that’s their opinion.”

Jones’ prison writings recount his childhood in Compton, his spiritual journey as a condemned man and death row prison food, among other topics.

(Courtesy of Albert Jones)

Jones could have filed away his writings in a box, to be shipped off to his family for their private consumption, perhaps sparing the Florville family more pain. But by making them available to a research institution, Jones said, the public might get a better understanding of California’s death row, including how prisoners built community, practiced religion, even grieved.

In one journal entry, Jones reflects on news that one of his friends died by suicide after a stint in solitary confinement: “He was in a cell for 14 days as punishment for whatever, but you’re supposed to get 10 days in that cell. On the fourteenth day, he killed himself,” Jones wrote. “I don’t know if you can go to heaven if you killed yourself, but I pray that he made it and that his family is at rest. God bless.”

Diego Godoy, associate curator of the California and Hispanic collections at the Huntington Library in San Marino, said the archive could be useful for scholars for many reasons, including to better understand prison culture.

“It’s part of history. It’s part of the human experience,” Godoy said. “And I think it’s worth preserving stuff like this and having it available for people to consult.”

In preparation for his New York trip, Kinmont spent a recent afternoon packing up boxes with Jones’ work. The materials seemed wildly out of place in Kinmont’s office, where hundreds of antique books lined towering shelves.

Three years ago, Kinmont helped coordinate the $2-million sale of an historic wine book collection to a wine company run by Prince Robert of Luxembourg. He once acquired the manuscript for a cookbook written by a woman who survived the Holocaust and collected recipes while living in a concentration camp. Yet working with Jones on his archive, Kinmont said, has been “the most profound experience of my professional life.”

“I’m not saying Albert’s a saint,” says Ben Kinmont, the bookseller auctioning Jones’ prison archive. “But I will say that he has accomplished something which very, very few people have.”

(Hannah Wiley / Los Angeles Times)

His hope is that Jones’ archive might show the world what kind of artistry and human connection is possible in a place designed to crush creativity and, ultimately, execute people.

“I’m not saying Albert’s a saint. I’m not in a position to say that,” Kinmont said. “But I will say that he has accomplished something which very, very few people have.”

As for Jones, he’s already diving into his next project, a book about his prison transfer out of San Quentin. He plans to title it: “Free at Last, free at Last. But I’m Still Condemned.”