As La Niña gathers strength in the tropical Pacific, forecasters are warning that the climate pattern could plunge California back into drought conditions in the months ahead.

La Niña is the drier component of the El Niño Southern Oscillation system, or ENSO, which is a main driver of climate and weather patterns across the globe. Its warm, moist counterpart, El Niño, was last in place from July 2023 until this spring, and was linked to record-warm global temperatures and California’s extraordinarily wet winter.

Though ENSO conditions are neutral at the moment, La Niña’s arrival appears increasingly imminent. There is a 66% chance it will develop between September and November and a 74% chance that it will persist through the winter, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

On the East Coast, that could mean a continued active hurricane season. But in the West — and particularly in Southern California — it could signal a return to dryness ahead.

“Drought episodes do wane and redevelop, and a lot of that is associated with La Niña,” said Brad Pugh, a meteorologist with NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center. “The good news is [California’s] out of drought currently, but with La Niña forecast through the winter, Southern California and the Southwest will be vulnerable for a redevelopment of drought.”

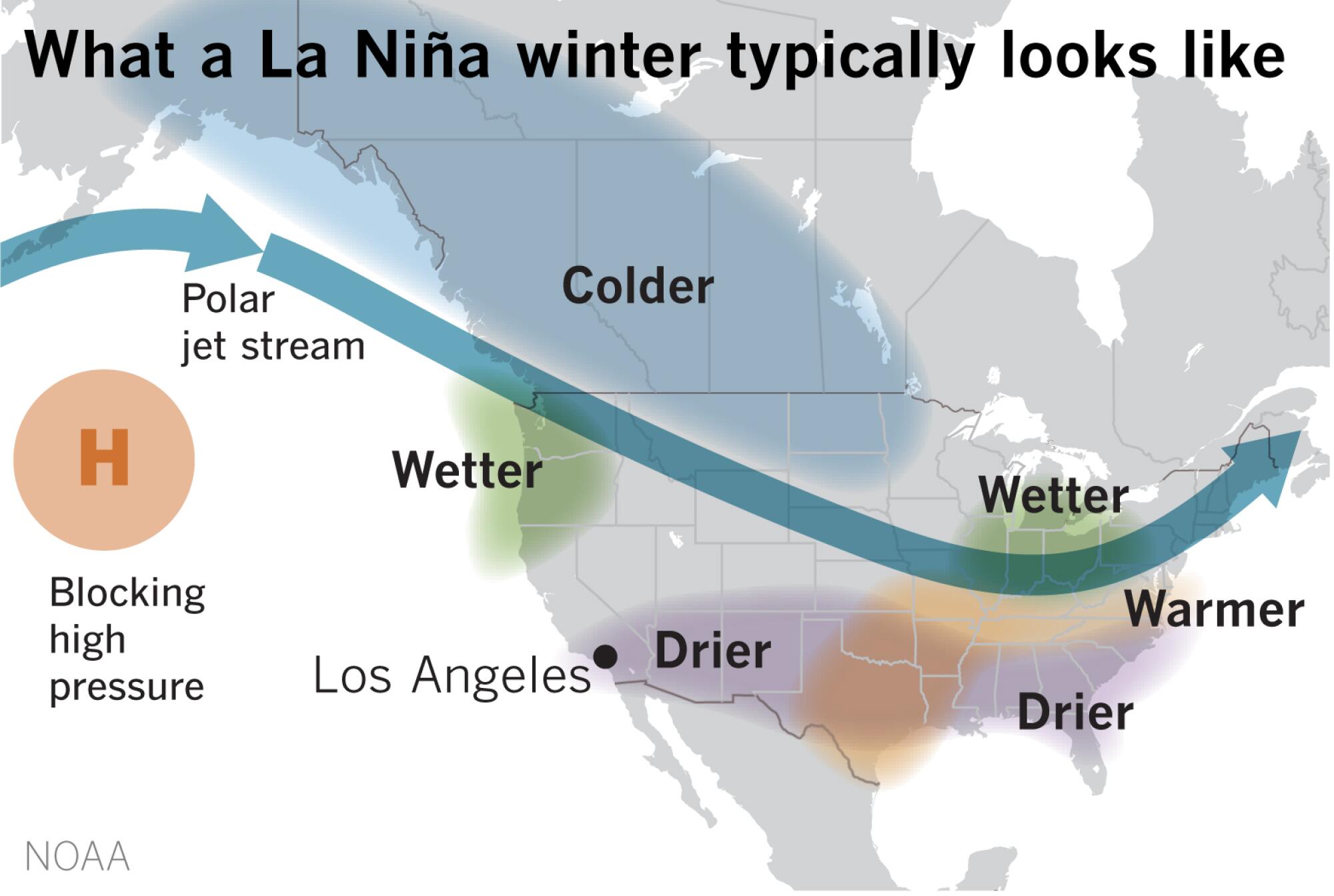

A La Niña usually means a drier winter across the southern United States.

(Paul Duginski / Los Angeles Times)

La Niña was last in place from 2020 to 2023 — a period of time that included California’s driest three years on record. The arid stretch shrank reservoirs to record lows, triggered Southern California’s strictest water restrictions ever and helped fuel the state’s worst wildfire seasons on record.

Recent months have already shown some backsliding into dryness, in part because record-smashing heat has been sapping moisture from the air and landscape.

Over the last eight weeks, “the demand of moisture by the atmosphere was exceptional due to warm temperatures,” Pugh said.

The latest update from the U.S. Drought Monitor shows about 17% of California now ranks as abnormally dry, compared with just over 1% three months ago.

However, there are no guarantees.

La Niña only tilts the odds toward dryness — it doesn’t ensure it — and its arrival has already been delayed from earlier projections.

In fact, just a few months ago, there was a high likelihood that El Niño would quickly transition into La Niña this summer.

“The thought was we would be probably in — or close to in — a La Niña by this point of summertime,” said Tom DiLiberto, an ENSO forecaster with NOAA. “We’re clearly not yet. We’re still expecting it to emerge, now in the fall.”

The sluggish start could be because the planet’s oceans are taking longer to cool after soaring to record-high temperatures over the last year. La Niña is partly defined by periods of below-average surface temperatures in the Pacific, as well as a northward shift of the jet stream — the atmosphere’s racetrack for storms from the Pacific.

“We haven’t seen both the ocean temperatures reflect that cooling enough … and we also haven’t seen the atmosphere hook on,” DiLiberto said.

Still, he is relatively confident La Niña will emerge because there is a large area of below-average-temperature water just beneath the surface of the Pacific Ocean, which is “slowly but surely approaching the surface,” DiLiberto said.

“So the signs are all still there,” he said. “It’s just, as opposed to jogging toward La Niña, we’re walking.”

La Niña’s effects also aren’t uniform.

While the pattern is associated with dryness in Southern California, its signal is more ambiguous in the Bay Area and northern part of the state. In the Pacific Northwest, it tends to lead to wetter-than-average conditions.

Nathan Lenssen, a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research and the Colorado School of Mines, said he’s hopeful La Niña won’t lead to another year of drought for California, especially given the explosive wildfires already seen across the state this year.

But he said people need to be prepared — both for drought and for other extreme weather events that are becoming more common because of human-caused climate change.

“What we also know is that intense storms are becoming more intense,” Lenssen said. “So for things like flooding, we’re still not out of the woods, even with the La Niña.”

Indeed, La Niña was also in place during the state’s record-wet winter of 2022-23, he noted.

Those hoping for relief from the planet’s simmering warmth will also have to wait a bit longer.

The latest seasonal outlooks published by NOAA call for above-normal temperatures across most of the continental United States through at least November — with the largest probability of above-normal temperatures in New England and parts of the Southwest.

The West Coast and Pacific Northwest show equal chances of above- or below-normal temperatures, the outlook shows.

The lack of cooling and delayed onset of La Niña could also have implications for the year’s overall temperature.

There is currently a 77% chance that 2024 will beat 2023 as the planet’s warmest year on record, and a nearly 100% chance it will be among the top five warmest years, according to Karin Gleason, monitoring section chief with NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information.

The forecast also points to continued dryness regardless of La Niña’s timing. Below-normal precipitation is likely through November for the Southwest and Southern California, as well as portions of the Great Plains, the outlook shows.

Pugh, of the Climate Prediction Center, said he’s still expecting La Niña to begin to exert its influence this autumn.

Its strength, however, has yet to be determined, with models showing a wide range of probabilities currently ranging from weak to moderate.

“If La Niña continues through the winter, we would expect drier- than-normal conditions over Southern California and the Southwest,” Pugh said. “So I would say that as we head through the winter, drought could redevelop in those areas.”

Newsletter

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.