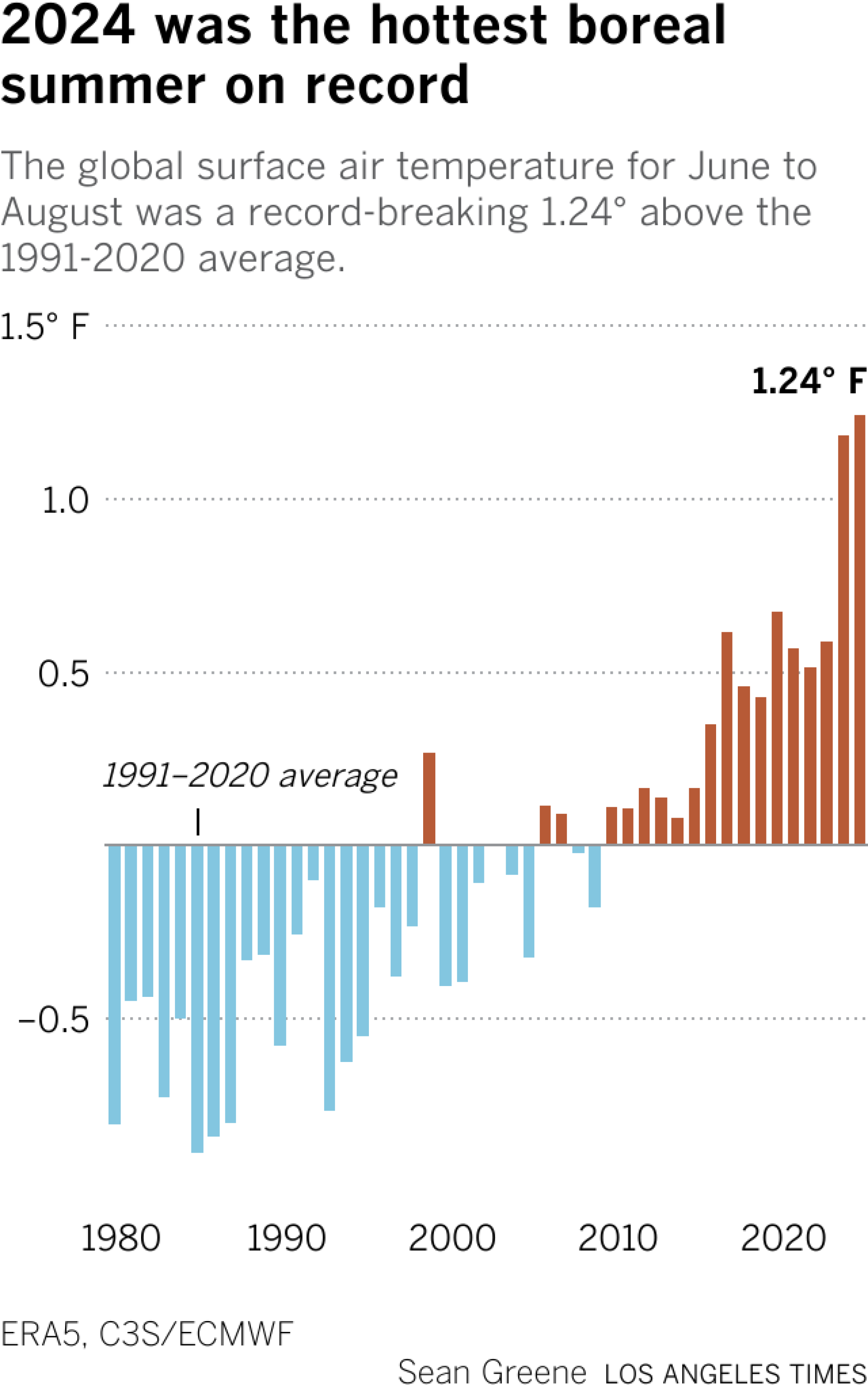

As Southern California swelters under its most punishing heat wave of the year, international climate officials have confirmed that summer 2024 was Earth’s hottest on record.

The global average temperature in June, July and August — known as the boreal summer in the Northern hemisphere — was a record-breaking 62.24 degrees, according to the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service. The season was marked by explosive wildfires, sizzling heat waves and heat-related deaths in California and many other parts of the world.

“During the past three months of 2024, the globe has experienced the hottest June and August, the hottest day on record, and the hottest boreal summer on record,” read a statement from Samantha Burgess, Copernicus’ deputy director. “The temperature-related extreme events witnessed this summer will only become more intense, with more devastating consequences for people and the planet unless we take urgent action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

Not only was it a hot summer, but August effectively tied 2023 as the planet’s hottest August on record with a global average temperature of about 62.28 degrees, the agency said.

In fact, the entire year to date has been so warm that even with four months to go, 2024 is now nearly certain to surpass 2023 as Earth’s hottest year on record.

That’s because the global average temperature anomaly from January to August was the highest on record for the period — and 0.41 degrees warmer than the same period last year.

The average anomaly would need to drop by more than half a degree for 2024 to not be warmer than 2023, which has never happened in the entire Copernicus data set, the agency said.

A woman sunbathes in a park in Milan, Italy, during a July heat wave.

(Luca Bruno / Associated Press)

The near-relentless string of record-hot months has left climate scientists and officials concerned as the planet hurtles toward a dangerous tipping point.

“We are playing Russian roulette with our planet, and we need an exit ramp off the highway to climate hell,” António Guterres, secretary-general of the United Nations, said during a speech at the start of the record-hot summer in June.

While Earth’s rising temperatures are somewhat consistent with the higher end of climate model projections, the heat has also defied some expectations, according to Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist with Berkeley Earth.

“The heat in 2024 has persisted longer than many of us expected, with the past few months tying the extremes we saw in the latter half of 2023,” Hausfather said in an email.

This is particularly perplexing because El Niño — a climate pattern associated with warmer global temperatures — dissipated toward the end of May but did not lead to an anticipated decline in global temperatures. Typically, there is a three-month lag between peak El Niño conditions and the global surface temperature response, “but even with that we should have already started cooling off a bit,” Hausfather said.

That conditions have remained steadily warm without El Niño may be an indication that additional factors are at work, he said. Some theories include a change in aerosol shipping regulations that allowed more sunlight to reach Earth; an uptick in the 11-year solar cycle; and the 2022 eruption of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha‘apai volcano, which may have trapped some heat in the atmosphere.

But even those factors “don’t seem to completely add up to what we are seeing,” Hausfather said.

Also concerning is the steady climb of temperatures beyond the international limit of 2.7 degrees, or 1.5 degrees Celsius, which was established by nearly 200 nations under the 2015 Paris climate accord in an effort to prevent the worst effects of global warming.

The limit is measured against the pre-industrial era, or the period before humans began to meaningfully alter the planet’s climate through greenhouse gases and other fossil fuel emissions, and generally uses temperature data from between 1850 and 1900.

August 2024 was the 13th month in a 14-month period to exceed that benchmark, with the global average temperature measuring roughly 2.72 degrees — or 1.51 degrees Celsius — above pre-industrial levels, according to Copernicus. The streak was broken only by the month of July, which came in just shy of the limit for the first time in a year.

Experts say a single year of warming over the limit does not mean humanity has officially exceeded the boundary, but it is a concerning trend that is moving in the wrong direction.

“It’s certainly a worrying sign that global temperatures have been persistently above 1.5 degrees Celsius for so long,” Hausfather said. He placed the probability of 2024 exceeding 2023 as the hottest year on record at greater than 95%, and said it is also very likely to be the first year above 1.5 degrees Celsius in the Copernicus data set, although other data sets may disagree due to slight differences in measurements.

Tourists walk with an umbrella in front of the Parthenon at the ancient Acropolis in central Athens, in June.

(Petros Giannakouris / Associated Press)

And while summer was marked by sweltering heat on land, the planet’s oceans also simmered. Record-warm ocean waters contributed to a violent start to the Atlantic hurricane season this year, with Hurricane Beryl becoming the basin’s earliest Category 5 hurricane on record when it formed in late June.

August also saw Arctic sea ice extent dip to 17% below average — the fourth-lowest for the month in the satellite record and “distinctly further below average than the same month for the previous three years,” Copernicus officials said.

Antarctic sea ice extent was 7% below average, the second-lowest extent for August in the satellite data record.

The report comes as Southern California endures several consecutive days of triple-digit temperatures, including highs over 110 degrees in some parts of Los Angeles County.

In fact, the summer was notably warm across nearly all of the Golden State, where July went down as California’s hottest month on record.

Officials in Death Valley National Park — where two people died of heat-related illness — confirmed that the park saw its hottest-ever summer with nine consecutive days of 125 degrees or hotter. The park’s average 24-hour temperature in June, July and August was 104.5 degrees, beating the previous record of 104.2 degrees set in 2021 and 2018.

Daniel Swain, a climate scientist with UCLA, said the current heat wave is likely to break some daily records in Southern California, which has largely fared better than the rest of the state during this year’s hot summer.

“It will almost certainly [bring] the hottest day of the year in a lot of Southern California, and perhaps even the hottest day in several years in some parts of Southern California,” Swain said during a briefing on Wednesday. “This is a significant heat event.”

Large swaths of the the region are also likely to see some of their warmest nights on record for the time of year, he said.

“It may not sound as dramatic as, say, the hottest days on record or the hottest afternoon peak temperatures, but those nighttime temperatures are quite consequential from a human health impact perspective, an ecosystem health perspective and also a wildfire perspective,” he said.

Indeed, heat is the deadliest of all climate hazards, and a recent study confirmed that heat-related deaths are on the rise in the United States.

The latest seasonal outlooks from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration indicate that above-normal temperatures may persist across nearly all of the country through at least November.

Already, residents in Phoenix, Arizona, have endured more than 100 consecutive days of temperatures over 100 degrees, shattering the previous record of 76 days set in 1993, according to the National Weather Service.